“Most new products are experiments and most experiments fail.” — Stewart Brand, “How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built.”

Stewart Brand’s caution in 1994 about using new products is engaging and controversial, since progress can only be made through the use of new products and innovative approaches. Brand’s caution echoes what forensic building consultants and building scientists have seen for decades: anything that departs from the “tried and true method” often fails. This isn’t surprising, since even traditional building materials experience some percentage of catastrophic failures form moisture and mold problems.

The warning is especially appropriate today with the expansion of new products, many intended for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED®) certification.

Although many of these “green” products have been developed within the last five years, they’re intended for use in buildings that should last for more than 50 years. Even a casual review of product literature indicates that some of these products appear to have had minimal on-site testing or performance verification. Additionally, many have not been marketed in a manner suggesting caution about regional or climatic restrictions in their use. Finally, we suspect that there has been even less testing of the complex, interrelated assemblies in which these products will be asked to co-exist for 50+ years or more.

Although some indicators of a building’s performance (comfort, energy usage, and odors) can be ignored, you can’t easily ignore water pouring through a wall assembly.

We don’t believe that anyone would view as sustainable any building that can’t survive the first five years without a major renovation due to moisture problems.

After reviewing the designs of hundreds of new buildings over the past 10 years and observing the failures in an equal number of structures, the authors have found the following consistent truths:

Building commissioning. The current industry approach to building commissioning (including LEED Enhanced Commissioning version Energy and Atmosphere (EA) Credit 3 — fundamental commissioning of the building energy systems and enhanced commissioning) is unlikely to prevent moisture and similar building failures in almost any climate, except for the most forgiving climates, such as low rainfall, moderate temperatures yearround, and minimal humidity levels. And even in those climates, specific building types could be expected to exhibit problems if best practices aren’t followed.

New materials. The use of many new and untested building products often has brought about unexpected performance that sometimes result in causing moisture accumulation and mold growth. Since wall and roof assemblies have historically been high-risk areas, it should be no surprise that the increased use of new products in these areas can dramatically increase the overall potential of moisture problems within the envelope.

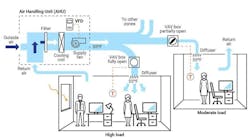

Increased building ventilation. The positive benefits of increased outside air ventilation for the occupant’s health and comfort can often be outweighed by the increased potential for moisture problems, some of which have caused catastrophic failures in the past.

Forensic engineers have strong evidence that buildings can perform in unexpected and damaging ways when additional air is moved through them.

Through our evaluation of various LEED credit opportunities for designers, we’re convinced that a sustainable building must be equally designed to prevent likely moisture and mold problems. We believe that a building attaining LEED certification isn’t necessarily a building with a low potential for failure due to moisture intrusion. However, it’s our belief that LEED certification can be combined with best practices for moisture and mold problem avoidance, but will require extra effort from both architects and mechanical engineers.

Benefits of HVAC & Moisture Control

An important aspect to avoiding moisture problems in green buildings is to include best practices from the waterproofing and HVAC disciplines in combination with the LEED certification principles.

It’s unwise to assume that LEED certification has automatically incorporated those best practices. Green building practices must always be subservient to best design practices in areas such as exterior waterproofing, good humidity control, and proper due diligence in selecting new construction materials.

Building commissioning (even the enhanced version of commissioning in LEED EA credit 3) isn’t likely to prevent catastrophic moisture and mold problems. Traditional commissioning fails to accomplish two primary requirements in avoiding moisture problems.

1. The traditional commissioning design review isn’t likely to be a “standard of care” technical peer review, but is more often a review intended to determine if the constructed building, once built, can be commissioned, and if the design meets the owner’s intent. In our experience the typical design review won’t predict the potential for moisture and mold problems. Without this prediction it can’t offer specific solutions to avoid them.

2. These reviews aren’t required to incorporate an analysis of the building envelope’s performance — the components acknowledged to fail most often, and usually most dramatically.

The building science industry has known for some time that moisture and mold problems are often predictable, even during the early design stage. However, for this analysis to be successful, the review team must be very savvy about what combination of design choices create a high risk of causing problems and what other choices are lower risks.

Some concepts that should be included in building commissioning to reduce the possibility of moisture and mold problems include the following:

- During the design phase, a technical peer review of the document should identify issues that will likely be major causes of moisture and mold problems in the operating building. This review may need to be done by someone other than the traditional commissioning agent, who may not have the requisite skill set for this type of analysis. This review needs to specifically identify which building components and systems have a high potential for moisture problems and offer alternative solutions to the design team.

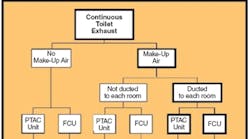

The commissioning process needs to consider the interrelationship of the building envelope and the HVAC system. This area is often overlooked because it involves understanding the dynamic interaction between two separate technology areas. - When commissioning the building envelope, both individual envelope components (such as windows) should be tested as well as assemblies of multiple adjacent components. Testing individual components doesn’t address connection points and intersections between various components where most failures occur. Assembly testing can include a mix of qualitative and quantitative testing, such as those used by ASTM International.

- Construction phase commissioning of building envelope components may require adjustment of installation methods based on test results. Checklists should be developed to certify adjustments are correctly implemented.

Various new strategies, while innovative, haven’t been sufficiently evaluated, especially where the potential for moisture damage exists. As a result, we’ve created conditions for increased incidences of building failures — with the risk increasing dramatically in certain climates. What’s needed is not to abandon the goal of more sustainable buildings, but to combine the best practices of what we already know in such areas as Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) and humidity control, with new and innovative green building recommendations. When these areas are in conflict, then the best practices model must always be chosen even if that means that LEED certification suffers. Only by analyzing building performance over the long term and resisting the urge to write uncritical success stories will we keep the green building movement on solid footing, and reduce impediments to its development.

In Part II: Use of New Materials in High-Risk Locations

The authors are principals with the Liberty Building Forensics Group, Zellwood FL. David Odom is a moisture and building forensics specialist and was honored as “Indoor Air Quality Person of the Year” by IAQ Magazine. He is the co-author of 3 books.

George DuBose is a mechanical engineer with more than 15 years experience in building systems. He served as a technical adviser for building commissioning to the Atlanta Committee for the 1996 Olympic Games. Richard Scott is a forensic architect specializing in green building design and building envelope performance. Over the past 20 years he has consulted on some of the largest building failure projects in the U.S.

The authors can be reached by calling 407/703-1300. Visit www.libertybuilding.com for additional information.

This article originally appeared in an expanded format in NCARB Magazine. Used by permission.