by Valerie Stakes, managing editor

In a time when many customers are clinging to their aging equipment, commercial contractors are challenged with finding the most appropriate, energy-efficient solutions for their large chilled water cooling needs.

According to Ash Awad, vice president of the energy services division at Mc- Kinstry Co. in Seattle, WA, carefully listening to their customers needs and then presenting options are keys to success.

“As an industry, we tend to stay a bit narrow and only offer those choices we’re most comfortable with,” he says. ”Clients deserve the opportunity to have different equipment options, and not just be guided down the traditional path of what we or they have always used.”

A thorough equipment analysis is also in order.

“Our division focuses on reducing our clients’ energy and utility costs, while improving their overall operation. This involves performing energy audits and engineering analyses, testing and monitoring, all of which lead to the implementation of cost-effective measures that allow us to secure utility rebates,” he adds.

“Whether it’s a CFC issue, failing equipment, or a need to increase capacity because of an increase in facility or building — we spend a lot of time listening to make sure we understand what our customers want and need,” Awad says.

Michael Johannes, manager of technical services at Owens Companies, Inc., in Bloomington, MN, adds that just looking at chiller replacement isn’t enough, particularly in buildings or areas where systems are pushing the 30-year mark.

“There is no ideal chiller; every project is different,” he says. “Although replacing chillers will improve energy efficiency, it won’t solve all potential problems. The key is to look at the facility as a whole,” he says.

At the onset of a project, the company performs a cooling system replacement study that examines the current system and how the needs of the facility have changed since the system was initially installed.

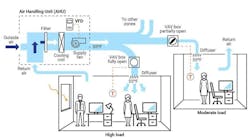

“We look at cooling loads, chilled water and condenser water piping and pumping systems, building ventilation, air distribution systems, environmental control systems, etc. Once the study is completed, we have a picture of the facility’s current HVAC requirements and the best method of how to proceed with the chiller replacements or any system modifications” Johannes says.

Alternatives in Cooling

Once you’ve determined your customer’s cooling needs, what shall it be: electric, gas, or steam? While electric-driven centrifugal chillers remain widely popular, the August blackout revealed an aging electrical grid, leading to fears over its reliability. For concerned building owners and plant managers, gas and steam cooling are alternatives.

Gas: “For some projects, gas cooling can be a great solution,” says Jeff Rosen, mechanical division manager at JF White in Framingham, MA.

However, Rosen stresses that availability and economics must be kept in mind. “For example, is gas readily available? If you have to run 100 miles worth of gas pipe, it’s clearly not economical. Also, what is the cost of gas versus electricity?”

Scott Smith, vice president of Emcor Services in Pompton Plains, NJ adds, “Gas can be a viable options for projects with an attractive rate structure or utility rebates. In those cases, I would use gas engine chillers because of their energy efficiency.

“Although maintenance costs are higher for gas engine chillers, this can be than compensated for by the improvement in efficiency,” he says.

Steam: In addition to gas, steam is a viable alternative to electric cooling, particularly for facilities with a readily available source of waste steam, such as a cogeneration plant.

“In the past, cogeneration plants tended to have steam-fired absorption chillers,” says Smith. “Today, you often see steam-turbine centrifugal chillers because you can get more use out of that waste heat by spinning a turbine than you can through the absorption refrigeration cycle.”

According to Mike Feutz, chair of the HVACR Department at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, MI, “When you have a turbine or engine running all the time, turning a generator to make power, and running the exhaust through a boiler to make steam, it’s a great source of heat during the winter,” During the summer, you can run an absorber for cooling.”

However, efficiency and expense are factors to consider. “Electric chillers are up to eight times more efficient than absorbers. Therefore, you should only use an absorber in applications where you have a source of excess heat, or where electricity is either unavailable or very expensive,” he says.

Feutz adds that one application includes facilities such as schools that weren’t designed to accommodate air conditioning and don’t have the electrical service required to run large electric chillers.

“Instead of running a new electric service, which might require tearing up a street to run a new line, it might be cheaper to put in an absorber, particularly in cooler climates where the air conditioning demand lasts only a few months,” he says.

Hybrid Systems: Another solution is to have a multi-chiller plant featuring both gas and electric chillers. Not only does it provide redundancy, but the costs of energy can be monitored and used during off-peak times.

“Having a gas/electric multi-chiller plant is a valid strategy,” says Smith. “However, some customers may have problems justifying a large amount of capital sitting around that’s not always being used.”

Service Concerns

When it comes to servicing large chillers, Awad states that electric chillers are viewed as easier to service, particularly by owners with an on-site maintenance staff.

“Our greatest challenge is educating customers on alternatives to electric chillers, and maintenance costs can drive many clients to the highest efficiency electric chillers they can afford at the time,” Awad says.

”For example, at Washington State University, one of our largest energy clients, we’re in the process of putting in 3,000 tons of cooling,” he says. The campus had steam absorbers, and McKinstry Co. suggested replacing them with gas chillers to improve efficiency.

“In the end, the owner wanted electric because he felt that his staff wasn’t capable of managing anything but electric,” says Awad.

According to Robert Frey, McKinstry’s service sales manager, a primary reason customers reject gas engine drive chillers or absorbers is installation costs. “A ‘normal’ electric drive centrifugal chiller usually costs about $800 per ton. A gas-engine driven unit is at least 112 to 2 times that amount, and an absorber is easily 5 times the normal amount,” he says. “In addition, very few customers have the on-staff engineers who know how to operate an absorber.”

Nevertheless, Awad stresses how it’s essential to have your staff trained to handle all varieties of chillers.

“We provide extensive technical training to technicians both in-house and through manufacturers,” says Awad. “Therefore, our customers know we can handle any of their needs, whether it’s now or 10 years down the road.”

When it comes time for your customer’s next chiller overhaul, it’s this experience and flexibility that can make your company the contractor of choice.

Valerie Stakes can be reached at 216/931-9439 or e-mail [email protected].