Most contractors have removed a newly installed piece of equipment and replaced it with a larger one to keep a customer happy, at least once. Years ago, we made the same mistake. This situation raises an interesting question. Why didn’t the first piece of equipment do the job? Undersized, you say?

Chances are the equipment size wasn’t the problem. Although, by our actions at the time, we believed equipment sizing was the issue.

Can a four-ton become a two-ton?

Unfortunately, more often than many of us know, what we believe is a four-ton system, may spend a portion of the day delivering less than 24,000 BTU of cooling per hour.

Just because the model number has a 48, is little assurance the system will deliver the four tons of cooling that the equipment is rated for. Equipment performance ratings are just one piece of the performance pie when it comes to delivering comfort.

When evaluating installed performance, the BTU removal process is invisible. From our experience in the industry, many of us simply believe our systems work according to equipment manufacturer’s engineering data. Very often, this isn’t the case.

We’ve had the technical training to troubleshoot and solve electrical and mechanical problems with the equipment, but the unseen flaws in a system are what cause us the most grief and leave our customers dissatisfied season after season.

To find and solve the disappearance of two tons of cooling, we need to step into the invisible side of the system and go beyond the box.

Solution Number One

The first group of problems to be addressed when it comes to performance is the mechanical or electrical defects. We have great confidence in your ability to solve these problems, so we’ll leave these equipment defects out of this article. Besides, we could fill a book with those possibilities, but most other industry trade organizations already have.

Solution Number Two

Your customer calls the office on a hot afternoon in mid summer. Here’s the complaint: “Our system works great in the morning, but then it won’t cool in the afternoon. Your guys have been out three times, they add refrigerant on each trip and nothing’s changed.”

So, is it the refrigerant charge that turns a four-ton system into a two-ton system? Maybe. The first step to getting the correct refrigerant charge is to get the correct airflow. With poor airflow, and a bogus refrigerant charge, the system satisfies the load in the morning, because the load is so low that the reduced capacity still does the job. When the afternoon heat hits, the system just can’t keep up.

Nearly every refrigerant charging table is created based on one single assumption. The assumption is that the technician followed the first rule of charging a system. The first rule is to verify that the system has the required airflow through it.

You can superheat and sub-cool to your heart’s content, but until airflow is corrected, you have no assurance the equipment or system can deliver the rated BTU that you sold your customer. Refrigerant charge correction without airflow verification has limited value.

So before replacing the equipment, verify that the airflow is correct. This takes less than five minutes. The three most used methods are to 1) employ an air balancing hood, 2) traverse airflow at an appropriate place near the fan, or 3) measure total external static pressure and plot airflow on the manufacturer’s fan performance table.

Solution Number Three

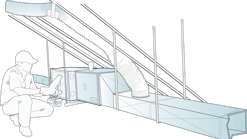

The equipment is working, but the building isn’t at the correct temperature. Duct systems frequently loose substantial amounts of cooling capacity to unconditioned space. While code requires R-38 in the attics in many parts of the country, code only requires R-4 or R-6 insulation on the duct system where the expensive air is found. That doesn’t make much sense, does it?

Most ACCA Manual J software seems to default to a 15% BTU loss under extreme conditions. In many buildings the temperature loss or gain may be 50% on the days you need the cooling the most.

In a live field situation, the answer is to measure the duct loss or gain under live conditions. The test is quick and easy. Visit the building on a hot afternoon and set the cooling function to “off.” Run the fan at the appropriate speed for ten minutes or so to allow the system and the building to stabilize. Notice the temperature change inside the building.

Then measure the average return grille air temperature. Say for example, its 70F. Next, measure the average supply register air temperature. Let’s say its 80F.

The system temperature change with the refrigerant system off and the fan on is 10F. Finally divide the 10F temperature change into the expected 20F temperature change of the cooling system when it’s on, and you’ll find the duct system is losing 50% of the equipment rated capacity. Once again, the four-ton is a two-ton.

Duct temperature loss during peak cooling hours has a massive impact on electrical consumption. Sadly, few government or utility programs are even aware that it can be measured and quantified. It can be measured in a few minutes.

The solution: Add additional insulation to these duct systems. Exceed code by a mile. When adding insulation in humid climates, apply practices that will assure there will be no moisture condensing on the ducts. Never use more than one moisture barrier.

So there’s the top three reasons a four-ton can become a two-ton. Are there more? Sure, tons of them, but time and space are limited here. Just be aware that next time your customer is complaining that they’re probably justified and that there are many more options to solving performance problems than installing larger equipment.

Rob “Doc” Falke serves the industry as president of National Comfort Institute a training company specializing in measuring, rating, improving and verifying HVAC system performance. If you're an HVAC contractor or technician interested in a free procedure to measure HVAC system losses, contact Doc at [email protected] or call him at 800-633-7058. Go to NCI’s website at nationalcomfortinstitute.com for free information, technical articles and downloads.